By: Audrey Gibbs

Trigger warning: This article discusses instances of sexual assault and rape.

In the new season of Catching Killers, an FBI agent stated that a murderer had a body count of eight—referring to the victims he had killed. Body count has become a phrase that doubles as a number of dead bodies and a count of sexual partners. This should raise an alarm in popular culture.

Body count is a phrase that is now undeniably tied to sex—but it wasn’t always. The term was coined by the U.S. military in 1962 during the Vietnam war, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. It meant “the number of killed enemy combatants,” or a count of the bodies of enemy soldiers.

In 1995, Vietnam released the official estimate of the number of Vietnamese killed in the war, with over a million fighters and 2 million civilians—all in all, about 12-13% of the country. The war is tied to images of bloody massacres and unethical power abuses. A man named Chuck Mawhinney held the highest body count, recording 103 kills in 16 months in Vietnam.

And now? In popular culture, the term body count means the amount of sexual partners one’s slept with. Urban Dictionary defines the term as:

1) How many people you’ve had sex with.

2) How many people you’ve killed.

During the Vietnam war, sexual misconduct was rampant. According to political science professor Karen Stuhldreher, rape of Vietnamese women by American soldiers was a “normal operating procedure.” GIs were rarely held accountable—and multiple witnesses say this was nearly an everyday occurrence for some soldiers. Sometimes, soldiers would kill these Vietnamese women as well, adding them to their body count. Perhaps this is where the term became inevitably tied to sex, and more specifically, sexual violence.

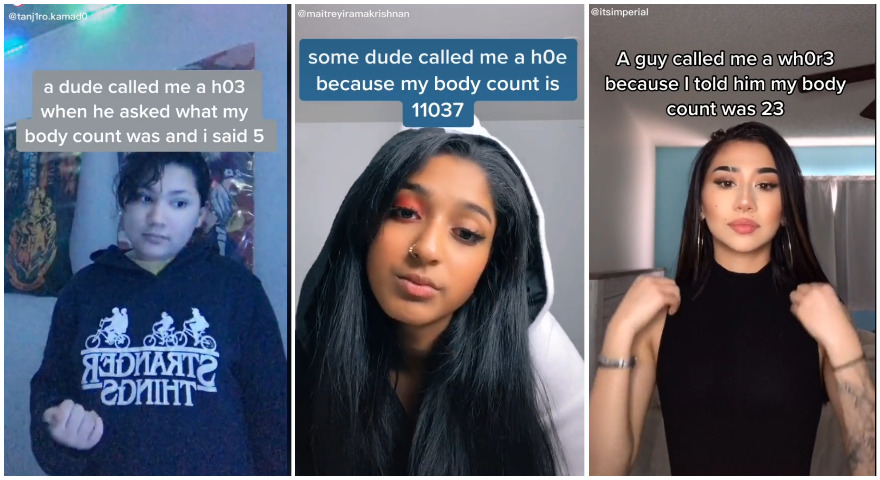

In 2020, the phrase surfaced on TikTok, used to refer to the number of sexual partners one has had—although it’s really often used only to refer to heterosexual penis-in-vagina sex. Notably, it was also the name of an American heavy metal band formed in the 90s in LA by Ice-T, and the title of a memoir by Sean Strub about the AIDS epidemic and the many who died.

To get to the core of why we talk about sex in the way that we do, In the Sheets reached out to Dr. Laurie Mintz for a Q&A. Mintz is a psychologist, emeritus professor of psychology at The University of Florida and sex therapist, as well as the author of Becoming Cliterate and a LELO sexpert.

In the Sheets: Have you seen body count on social media?

Dr. Mintz: Absolutely! I’ve seen it on social media on multiple platforms. It’s almost hard to avoid on TikTok but is also prominent on Instagram. I’ve seen videos of people debating if it matters what a woman’s body count is, videos of men saying not to date women with multiple body counts, and women saying men are only threatened by body count because they don’t want to be compared to other men.

Other viral trends include people asking strangers what their body count is and people joking about what they could purchase if their body count were dollars.

In the Sheets: It’s my understanding that this term has been popularized by all genders and that it refers to all different kinds of relationships—what do you think this means for culture at large?

Dr. Mintz: Honestly, I’ve not seen this expansion as much as I have seen the heteronormativity around the phrase, where body count is routinely used to refer to heterosexual penis-in-vagina sex. In fact, this is one of the big critiques I have seen about the word (among many others)—that it is inherently heteronormative in that most people use it to refer to penis-in-vagina sex.

So, if indeed this word is being popularized by all genders, I see both positive and negative in that. The positive is GLBTQA+ folks saying that the sexual encounters they have count as sex too, and one does not need to put a penis in a vagina to count it as sex. The negative is that this term is very problematic on a number of levels, so seeing it expanded even further is troubling.

In the Sheets: How do you believe phrases like this change the societal conversations around sex?

Dr. Mintz: Let’s start with the negatives:

- When considering the origin of the word, it equates sexual partners to conquests and even worse, it has violent connotations. This phrase is dehumanizing – turning people into bodies to conquest and count (and then discard) rather than humans with feelings to share pleasure with.

- It is often used to shame women, in that women who have “high body counts” are often judged more harshly than men with “high body counts.” Conversely, men with “too low body” counts are also often shamed.

- It creates anxiety and comparison – I’ve talked to people who worried their count was too high or too low, when in reality, the number of sexual partners a person has is their own choice and their own business.

- It’s a personal question for many, yet people have started asking this of strangers and people they just met or are on a date with for the first time.

- It’s generally used in a heteronormative way.

On the positive, it may mean we are more open about admitting that people actually do engage sexually. Still, I personally think there are less dehumanizing and less shaming ways to get this message across.

In the Sheets: What changes have you noticed, in your professional opinion, about how we talk about sex in recent years?

Dr. Mintz: I’ve been teaching Psychology of Human Sexuality to hundreds of undergrad students a year for about 12 years. I’ve noticed: less slut shaming of women, more awareness of the orgasm gap, more awareness of women’s pleasure including of the clitoris, more acceptance around GLBTQ+ identities.

At the same time, I’ve continued to hear horrific stories—particularly from women. These stories range from hookup sex in which their pleasure was not prioritized to sexual assault and coercion. As just an example, through anonymous polling in my most recent class, 44% of the women reported being in a scary situation during sex and/or been choked or slapped without their consent.

So, in short, we may talk more about sex in an accepting and open and less shaming way, but there are still many problems stemming, in my opinion, from a lack of scientifically accurate sex education coupled with the ready access to porn.

In the Sheets: Do you think conversations around sex, in recent years, have been more open and accepting?

Dr. Mintz: Honestly, I think it depends on where the conversations are happening. I see progress due to hosting a sex-positive social media platform and surrounding myself with similar people. However, many of my students tell me that they come from families and cultures where sex is not talked about and openly shamed.

There is a huge difference between being sex-positive and sexually objectifying. Sex-positivity means allowing yourself and others to learn about their sexuality, free of shame and judgment. Objectification, on the other hand, is inherently sex negative.

Open and accepting conversations around sex do not need to—and should not—include objectification or oversexualization of others.

In the Sheets: What would you say to people using terms like “body count?”

Dr. Mintz: I’d ask them to consider the following questions:

- What do you mean by this? What acts count? Why are you defining it this way?

- What does your “body count” mean to you?

- What does someone else’s “body count” mean to you?

- Do you shame others for their “body count”?

- Do you use it in a way that dehumanizes others or makes others into a conquest?

I’d ask them to think about if this term is inclusive, intersectional and sex positive. I’d ask them to consider if they are perhaps unwittingly using terminology that is actually not consistent with their values or that is harming themselves or others.

Dr. Mintz ended on a powerful note, emphasizing the fact that the way we talk about sex impacts societal perceptions of it. “I’d tell them that language both reflects and perpetuates culture, and it also has the power to change culture,” said Mintz.

Header photo credit: Sade Spence with stayhipp.com